Overview

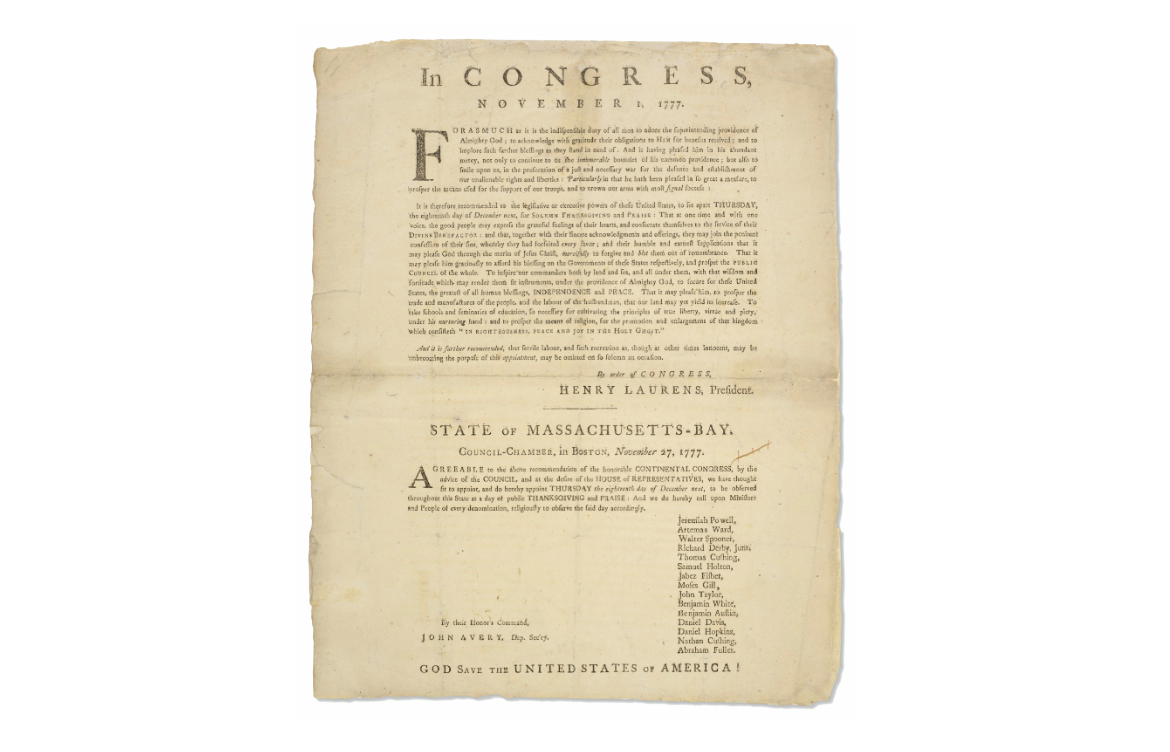

On November 1, 1777, the Second Continental Congress, which was convening in York, Pennsylvania following the British capture of Philadelphia, proclaimed a national day of thanksgiving and praise to celebrate the American victory at Saratoga.

On November 30, 1777, General Washington, the commander-in-chief of all Continental forces, issued General Orders designating December 18, 1777 – a day that was observed by all thirteen states – “for Solemn Thanksgiving and Praise”.

The day was set aside “to inspire our Commanders both by Land and Sea, and all under them, with that wisdom and fortitude which may render them fit Instruments, under the Providence of Almighty God, to secure for these United States the greatest of all human blessings, independence and peace.”

The First National Thanksgiving

The first nationwide call for a Thanksgiving came at a critical moment in the early history of the United States. The Continental Congress had declared independence nearly a year and a half before, and, save for a few notable exceptions, American arms endured a string of humiliating losses. The fall of 1776 saw the loss of New York City and Washington’s retreat across the Jerseys—a move that prompted Congress to flee Philadelphia fearing the British would overrun the American capital. Only Washington’s timely raids on Trenton and Princeton at the close of that campaign ensured that his rapidly-dwindling force would not completely disintegrate. The Campaign of 1777 would prove to be worse, at least for the main army under Washington. After a summer of indecisive maneuvers in Northern New Jersey, the British would move against Philadelphia in the late summer by way of Chesapeake Bay. Defeated at Brandywine in September 1777, Washington was unable to prevent the British from seizing the city, forcing Congress to once again evacuate, relocating to York, Pennsylvania. Washington would spend the remainder of the campaign in a vain attempt to dislodge the British from the American capital.

Meanwhile to the north, a large army under the command of John Burgoyne had been marching southward from Canada threatening to cut off New England from the rest of the country. By early September 1777, Burgoyne had taken Fort Ticonderoga, traversed Lake George and was now moving on Albany, where he planned to link up with British forces who were to advance northward from New York City. At Saratoga however, Burgoyne’s advance met stiff resistance from a large army commanded by Horatio Gates. Following two major actions, the first at Freeman’s Farm (19 September) and the second at Bemis Heights (7 October), Burgoyne found his army surrounded and out of options. On 17 October 1777, with no prospect of assistance from British forces in New York City, Burgoyne surrendered nearly 6,000 British and German troops together with a large stand of muskets and field artillery. The surrender at Saratoga proved one of the most important moments of the War of Independence. Within two days of the news arriving at Versailles, Louis XVI authorized negations for a formal alliance with the United States—opening the door to the French support that would fundamentally alter the balance of power and ultimately ensure American independence.

The news of Saratoga could not have reached Congress at a better moment. With the two largest American cities under British occupation, and Washington’s army on the verge of starvation, it was a dark time for the twenty or so delegates of the Continental Congress – who had fled to York, Pennsylvania – some of whom spoke openly about the prospect of total defeat. The first reports of Burgoyne’s surrender arrived in York in the final week of October—prompting Samuel Adams to write to a friend in Massachusetts, “Our sincere Acknowledgments of gratitude are due to the Supreme Disposer of All Events. I suppose Congress will recommend that a Day be set apart through out the United States for solemn Thanksgiving.”1 When further details of the terms of the Saratoga capitulation arrived days later, Congress nominated Adams together with Richard Henry Lee and Daniel Roberdau to draft a formal recommendation “a day of thanksgiving, for the signal success.”2

Widely-regarded as its primary author of the resolution recommending a thanksgiving, Samuel Adams drew his language from a long tradition. Days of thanksgiving have deep roots in both European and aboriginal cultures and traditions. Not only did British colonists observe thanksgiving to mark the passing of military victories and good harvests, but so too did French and Spanish colonists beginning in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. For New England, thanksgiving, as well as days of fasting, humiliation, and prayer in times of famine, war, or disease, were proclaimed on a somewhat frequent basis in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries—although colonies further afield proclaimed similar observances.

Although the celebration of thanksgiving often included a feast shared with family and neighbors, they were, as evidenced in the present text, first and foremost, solemn religious observances. Indeed the victory at Saratoga felt like a religious deliverance— especially following the long string of military disappointments that preceded it. The Reverend Timothy Dwight, preaching in Stamford, Connecticut on 18 December, compared the defeat of Burgoyne to Hezekiah’s successful defense of Jerusalem against the Assyrians.3 Meanwhile in neighboring Greenwich, David Avery, an army chaplain who had been present at Saratoga, gave a lengthy recounting of the entire conflict starting with Lexington and Concord, demonstrating each victory (and loss) as a sign of divine intervention.4

In his general orders for 17 December 1777, Washington announced that the army would be taking up winter quarters. After offering words of encouragement to his starving troops, he announced that “Tomorrow being the day set apart by the Honorable Congress for public Thanksgiving and Praise; and duty calling us devoutely to express our grateful acknowledgements to God for the manifold blessings he has granted us—The General directs that the army remain in its present quarters, and that the Chaplains perform divine service with their several Corps and brigades—And earnestly exhorts, all officers and soldiers, whose absence is not indispensibly necessary, to attend with reverence the solemnities of the day.”5

Henry Dearborn (1751-1829), then a young lieutenant in the 1st New Hampshire Regiment and a veteran of Saratoga, recorded the day vividly in his journal:“18th the weather still Remains uncomfortable—this is Thanksgiving Day thro the whole Continent of America—but god knows We have very Little to keep it with this being the third Day we have been without flouer or bread—& are Living on a high uncultivated hill, in huts & tents Laying on the Cold Ground, upon the whole I think all we have to be thankful for is that we are alive & not in the Grave with many of our friends” Considering the meager rations available, the Thanksgiving ‘feast’ was a scant one: “we had for thanksgiving breakfast some Exceeding Poor beef which has been boil.d & Now warm.d in an old short handled frying Pan in which we ware Obliged to Eat it haveing No other Platter—I Dined & sup.d at Genrl. [John] Sulivans to Day & so Ended thanksgiving.”6

Meanwhile, Lt. Samuel Armstrong, also a Saratoga veteran, complained that he “had neither Bread nor meat ’till just before night when we had some fresh Beef, without any Bread or flour, The Beef wou’d have Answer’d to have made Minced Pis if it cou’d been made tender Enough, but it seem’d Mr. Commissary did not intend that we Shou’d keep a Day of rejoicing—but however we Sent out a Scout for some fowls and by Night he Return’d with one Dozn: we distributed five of them among our fellow sufferers three we Roasted two we boil’d and Borrowed a few Potatoes[.] upon these we Supp’d without any Bread or anything Stronger than Water to drink!”7

The observance of this first national Thanksgiving, despite the privation and suffering, would be followed by a series of events that would transform the struggle for independence. Three days after Washington’s troops celebrated their meager feasts, they marched into Valley Forge to construct huts for their winter cantonment. Although the winter was a relatively mild one, poor planning, inadequate sanitation, and a lack of hygiene among the poorly disciplined soldiers allowed disease to take its toll—killing nearly 2,000 before the army broke camp in June 1778. But the relatively mild winter also allowed the newly-arrived Prussian drillmaster Baron von Steuben to transform the Continental Army into a disciplined fighting force. Soon after the Continental Army broke camp at Valley Forge, they encountered the British army on the field at Monmouth where they fought to a draw—an unimaginable outcome in the previous campaigns—and a direct result of the new manual of arms introduced by Von Steuben that winter. And two years later, the army’s newfound discipline would allow them to endure the worst winter of the eighteenth century during their cantonment at Morristown, New Jersey. The Army’s close attention to camp sanitation, hygiene and proper housing during the harsh winter of 1779-1780, widely considered the worst winter of the eighteenth century, allowed Washington’s troops to endure weeks of sub-freezing temperatures and near starvation while losing less than 100 dead.8

The lessons learned at Valley Forge allowed Washington to hold his army together as the he awaited the promise of the French alliance, secured by the victory at Saratoga, to bear fruit. The wait would prove long and frustrating, but since the first Thanksgiving of 1777, they were now better equipped to endure the disappointments and missed opportunities of those early years of the Franco-American alliance. That perseverance, in the face of cold, starvation, mutiny and even treason, would ensure that the victory at Saratoga, the cause for the first national Thanksgiving would not have been observed in vain.

1 Samuel Adams to Samuel P. Savage, 26 Oct. 1777, in Massachusetts Historical Society Proceedings, (Feb. 1910), vol. 43, p. 31.

2 Continental Congress, Journals, 31 Oct. 1777.

3 Timothy Dwight, A Sermon Preached at Stamford, in Connecticut, upon the General Thanksgiving, December 18th. 1777 (Norwich: Green & Spooner, 1778).

4 David Avery, A Sermon, Preached at Greenwich, Connecticut on the 18th of December 1777 (Hartford: Printed by Watson and Goodwin, 1778).

5 George Washington, General Orders, 17 December 1777, in John C. Fitzpatrick, The Writings of George Washington (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1933), vol. 10, p. 168.

6 Lloyd A. Brown, Howard H. Peckham, Revolutionary War Journals of Henry Dearborn, 1775-1783 (Chicago: The Caxton Club, 1939), p. 118.

7 Joseph Lee Boyle, “From Saratoga to Valley Forge The Diary of Lt. Samuel Armstrong,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 121, no. 3 (July 1997), p. 257.

8 Russel Frank Weigley, Morristown, National Historical Park, New Jersey (Washington: National Park Service, 1983), p.59.